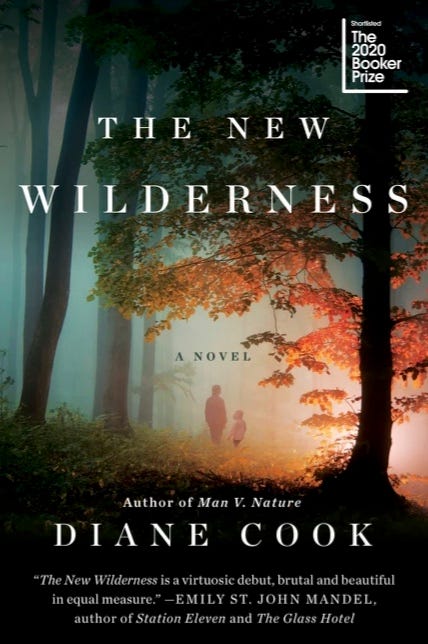

Book review: The New Wilderness tests whether man and nature can co-exist

Jack Hamilton imagines himself at the edge of civilization as in Diane Cook's new climate fiction novel.

By John Maxwell Hamilton

(About the author: John Maxwell Hamilton, the Hopkins P. Breazeale Professor of Journalism at Louisiana State University, is a longtime journalist and author of Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda.)

PARATY, Brazil (Callaway Climate Insights) — They have fled in desperation from the City. They are 20 men, women, and children, oppressed by streets and buildings overflowing with people, filth, vermin and danger. They are part of a “an experiment to see how people interacted with nature, because, with all land now being used for resources – oil, gas, minerals, water, wood, food – or storage – trash, servers, toxic waste – such interactions had become lost to history.” [p. 51] The overbuilt City has run out of sand for concrete. They were headed to the Wilderness State, the last untouched spot.

As it happened, I read The New Wilderness in settings that poignantly captured the conditions it described. I began reading the dystopian novel in Sao Paulo. The city of 44 million has the allurements of ebullient music and saporous food, but also perpetual traffic jams, deep poverty in crammed favelas, and endless concrete.

Scanning the cityscape from the top of one of Sao Paulo’s tallest buildings, I saw a monotonous, choppy sea of gray buildings spreading toward the distant mountains.

On the other side of those mountains, however, lie vast tropical forests. I finished the book here, on the edge of one of them, near the town of Paraty, with a population .001 the size of Sao Paulo. My rented house clung to the side of a steep slope on Brazil’s Costa Verde. Only a few homes were visible on the humpbacked islands that dotted the blue water and on the far shores of the bay. As expected of a region called Costa Verde, the dominant color on land was green, in every shade possible.

Government climate reports give us the data on overdevelopment and people-driven global warming. With travel we observe the consequences. In locale after locale, we see the delicate balance of nature teetering. And now a third lens is broadening our understanding of a world that is being paved over. Climate fiction, says Regina Marler in the New York Review of Books, “is a genre of necessity — a new, rapidly expanding chorus of alarm.”

The New Wilderness, one of these novels, tells the story of Beatrice, her daughter Agnes, and her partner Glen. They have taken the daring leap from the fetid City to restore Agnes’s health. The 20-person Community scratches out a primitive existence under close supervision and strict rules.

The Community must not stay very long in any one place, no matter how comfortable. Rangers in neat uniforms arrive in shiny trucks or on the backs of imposing horses to issue instructions on where to move next. “There is nowhere that you are allowed to just wait,” a note-taking Ranger scolds them when they resist. “You’re nomadic.” [p. 278] Each time they pack up to leave, their camp must be swept of all signs of their having been there. Time becomes unimportant in Wilderness State. Bea loses track of Agnes’s age. Memories of simple things like pillows fade. Clothes are soon in tatters, and the Community must make their own. They drown in swollen rivers or fall irretrievably into ravines. Sex becomes a weapon to establish dominance, as Bea does by moving to the bedroll of Carl, the nominative leader, but not up to the job. It is her way of protecting her daughter and Glen, whom she must nevertheless put out of his misery when he breaks his leg.

The population of Wilderness State increases, first with a handful of Newcomers and then, when the Wilderness State waitlist has grown impossibly long, with 2,000 illegal immigrants who have broken out of the City. “We’ve run across two former presidents here!” one Trespasser tells Agnes, adding they also stumbled on a movie star famous for action films. “But he was a mess. I can’t imagine he survived.” [p. 381]

For Bea the objective is to find a way to make yet another leap, to the Private Lands, a whispered, secret place “for the wealthy and powerful, where they could have their own land and do as they wished.” [p. 46] The chance comes when the Rangers announce that the experiment is over, and all must return to the City. But Agnes refuses to go to the Private Lands. Her distraught mother goes with the seemingly friendly Ranger Bob who has arranged the escape.

The mother-daughter estrangement has brewed for many seasons. Agnes both loves Bea and hates her opportunism at the expense of Glen and herself. Agnes, who proves to be an even more adept leader than her mother, has grown into a healthy self-confident creature of the wilderness. She skillfully kills and skins squirrels and deer. She savors the taste of wild onions. With keen instincts for survival, Agnes does not trust Ranger Bob. Unwilling to bend to any authority but her own, she declares her freedom, even if it means she must live a fugitive existence in the New Wilderness.

Author Diane Cook, who specializes in nature writing, delved deeply into the cultural and culinary histories of tribal cultures when researching The New Wilderness. This enriches the novel. Its grip on the reader — a grip that lasts from the first page to the last — is powered by the disturbing questions Cook raises and only gradually allows to be answered. The book was a Booker Prize finalist but could as easily have competed for a mystery writing award.

One of the last mysteries is unveiled when the impatient head Ranger explains why the Wilderness State experiment has been terminated. “The study,” he says, “has clearly shown that you can’t have a Wilderness with people.” [p. 355]

As I shut the book, I could hear the sounds of hammers and electric saws somewhere on the slopes nearby. The construction was shrouded by the dense jungle canopy — for the time being.

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook (HarperCollins) goes on sale June 22.