Climate-friendly corporations and the ghost of Milton Friedman

How less regulation could lead to some companies performing better on climate

(Mark Hulbert, an author and longtime investment columnist, is the founder of the Hulbert Financial Digest; his Hulbert Ratings audits investment newsletter returns.)

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. (Callaway Climate Insights) — How is it that some companies are able to be far more climate-friendly than their polluting competitors and yet remain just as profitable?

That conundrum is the focus of just-completed research into corporate social behavior in a lenient regulatory environment. Climate-friendly companies often pursue technologies and capital projects that have lower returns on equity. And while those technologies and capital projects are beneficial, they produce public goods that benefit everyone rather than those companies’ balance sheets. So how can these firms remain competitive?

This study that attempts an answer, which the National Bureau of Economic Research began circulating in December, is titled “Corporate Social Responsibility and Imperfect Regulatory Oversight.” Its authors are professors Jean-Etienne Bettignies of Canada’s Queen’s University, Hua Fang Liu of Canada’s Brandon University, and David Robinson of Duke University.

The researchers approach this big mystery by focusing on a smaller one: The reaction of U.K. corporations to a 2013 law (the so-called “Companies Act”) that mandated disclosures of greenhouse gas emissions. Relative to non-U.K. firms that were not subject to this Act, U.K. firms’ Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) ratings went down following this legislation’s enactment.

To understand why, the professors developed a complex model of the incentives that could lead corporations to go beyond what would otherwise be required by environmental laws and regulations. Those incentives include a willingness on the part of a large number of workers to be paid less when working for an environmentally-friendly company than for an unfriendly one, and a willingness by some investors to accept a lower return when owning such a company’s stocks and bonds.

Their willingness is what allows a pure profit-maximizing company to look like a purpose-driven one. An actual social or moral motivation is not required. It’s the workers’ and investors’ willingness to accept lower returns that enables these firms to go beyond what the law mandates and remain competitive with others that have lower CSR ratings — which must pay higher wages and promise higher returns on their equity and debt.

Readers interested in the details of the professors’ model should read their original study. But notice that a key consequence of their model is that, when all companies are held to a much higher standard, an individual company’s incentives to go further than its competitors will diminish — if not disappear. That’s what happened in the U.K. following the 2013 Companies Act.

If the professors’ model is a good one, then it must also be the case that firms with higher CSR ratings will be able to pay lower wages and salaries than their lower-rated competitors. This implication has been borne out by several previous studies: One that the authors of their new study refer to found a “44% decrease in wage bids submitted by workers after learning about the employer’s CSR activities.” Another found pay differentials between 24% and 38%.

Another implication is that investors in environmentally-friendly corporations will have a lower return over the long run, on average, than investors in less climate friendly firms. In an interview, Robinson said that he and his fellow researchers didn’t investigate that implication, in part because it is so difficult to separate out all the various factors that influence returns. Nevertheless, he said, a willingness to accept lower returns is a necessary precondition if climate-conscious investors want to nudge profit-maximizing corporations in the direction of becoming more environmentally friendly.

This is a recurring theme in my columns, as you will recall. As I have stressed, this willingness doesn’t mean that you should actively seek out lower returns. It’s your willingness that is crucial. It extends to companies a longer leash that allows them to pursue more climate friendly policies than otherwise.

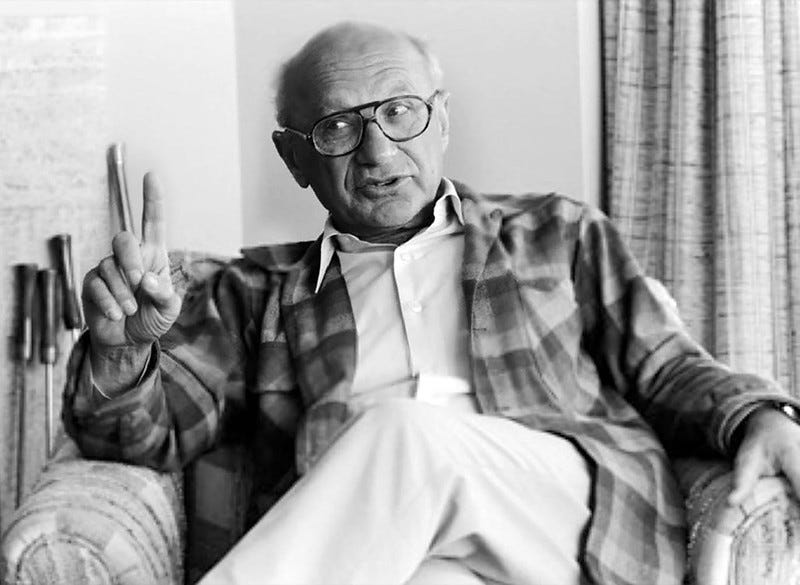

The ghost of Milton Friedman

This new study sheds an entirely new light on the famous argument advanced more than 50 years ago by the late economist (and Nobel laureate) Milton Friedman. He railed against the then-nascent CSR movement by insisting that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game.”

This new study instead shows that there is no inherent contradiction between being profit maximizing and pursuing climate friendly policies. On the contrary, according to the professors, “it is precisely the profit-maximization by a self-interested [businessperson] advocated by Friedman” that can in certain circumstances lead a firm to become more socially responsible.

It’s also worth reflecting that, because technological change is ever-accelerating, governments are at an increasing disadvantage in formulating regulations that remain up-to-date and relevant. And in an increasingly globalized world, national governments are finding it harder and harder to enforce those rules. Friedman’s reference to “rules of the game” seems outdated, even naïve. “When the rules of the game are poorly enforced,” the professors argue, CSR “can arise when firms behave exactly as Friedman suggested they should.”

Once again, however, it is you and I who are key: Are we willing to extend a long-enough leash to companies that would allow them to pursue the climate-friendly policies that, in a perfect world, regulators would require them to — and to still remain competitive?