Climate Threats to The World’s Busiest Seaports

Sea level rise, cyclones, and more threaten the future of the world’s busiest ports -- most of them in China -- and the global shipping industry.

SAN FRANCISCO (Callaway Climate Insights) -- With sea level rises of one to three feet forecast as a result of human-induced climate change by 2100, the world’s shipping industry is facing decades of adaptation and mitigation.

Estimates from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) put the amount of merchandise and materials moving by sea at some point during the production cycle at more than 80%.

Not surprisingly, a huge portion of that moves through ports in China.

Higher water levels obviously pose direct threats to existing port infrastructure, berths, storage areas, ground transport etc. But even assuming those risks are mitigated, the facilities will still be more vulnerable to storm damage from higher waves overtopping protective barriers, and storm surges in areas prone to tropical cyclones.

That’s all the more troublesome because so many of the world’s busiest container seaports are located in Asia, in areas at risk of being hit by cyclones.

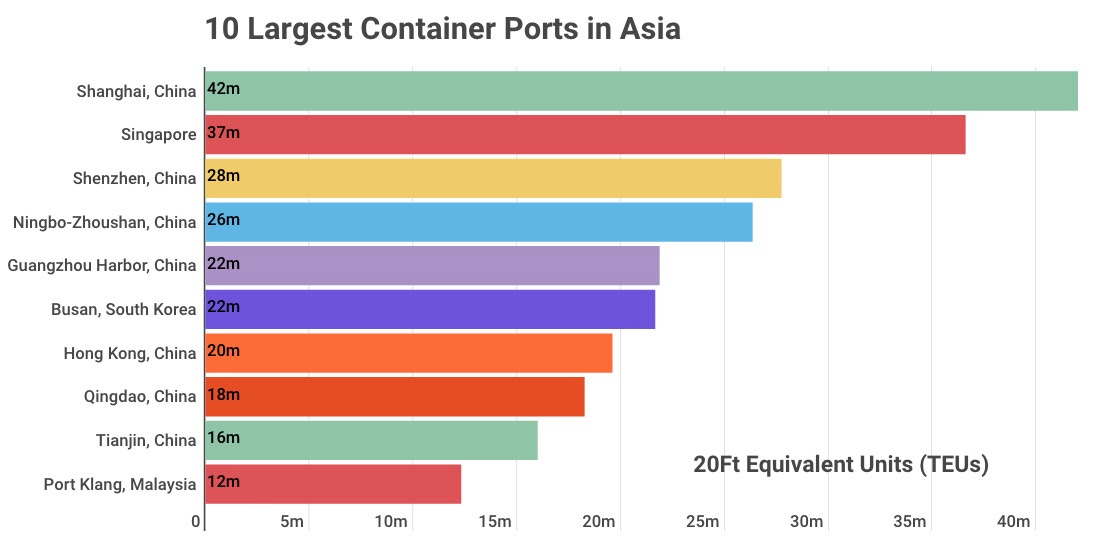

Based on world shipping council data through 2018, six of the 10 busiest ports are in China — seven, if you include Hong Kong. The deltas of the Yangtze, Yellow, and Pearl rivers serve as the receiving areas for bulk materials from around the globe and as staging areas for the enormous quantities of goods and products headed for Europe and the U.S.

All told, the 10 busiest container ports in Asia handle more than 240 million TEUs (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units). Shanghai alone moves more than 17% of that.

Storm-surge damage can be significant. In the case of Superstorm Sandy, the sea level rise of 10 inches at the foot of Manhattan resulted in 30% in additional damages, according to Lloyds of London.

And based on data from UNCTAD, virtually every one of the major Asian ports, as well as scores of smaller one, are within 50 km of where a tropical cyclone has struck.

Further risks abound in the so-called hinterlands, the regions backing up ports that see the passage of goods and products over roads and rail networks, as these too may be at risk from rising waters and storm damage.

The good news, from China’s point of view at least, is that adapting its ports to higher water levels is relatively inexpensive. The potential costs to raise major ports in mainland China were estimated at $2.5 billion to about $4.7 billion in a 2018 study by Asia Research & Engagement commissioned by HSBC. Including. Including Hong Kong, the estimates range from $5.2 billion to $8.5 billion.

By contrast, estimates for adapting Japan’s ports ranged from $13.8 to $23.3 billion. The difference is largely because China benefits from far lower construction and labor costs and because its port facilities tend to have less warehousing space, which is more expensive to rebuild at higher levels, according to the report.

No single U.S. port makes even the top 15, but when combined Los Angeles and Long Beach add up to about 17.5 million TEUs, which would be just enough to make the top 10 list globally.

In the case of Europe, the largest single port, Rotterdam, once the world’s busiest, now ranks 11th. When combined with nearby Antwerp, the two would be in fifth position globally.

Rotterdam also offers special insight into the kinds and scale of adaptation to climate change that may lie ahead.

Because so much of Holland is below sea level, the region has centuries of experience building dikes to protect and maintain the region. Since World War II, two huge infrastructure projects have been built over a period of decades, to protect the area from high water induced by big storms.

Similar barriers have been built on the Thames river, to protect London, and near Venice as part of the unending battles to protect that city. Galveston, Texas is also in the process of evaluating measures to protect low lying areas with high concentrations of oil industry assets using extensive sea barriers.