Food for thought about U.S. climate politics

This column introduces Bill Sternberg, former editorial page editor at USA Today, to our growing stable of writers. It's a sneak peek for subscribers only, to be published in Tuesday's newsletter.

This column is for subscribers only, but it’s OK to forward once in a while. Was it forwarded to you? Please subscribe here.

By Bill Sternberg

(Bill Sternberg is a veteran Washington journalist and former editorial page editor of USA Today.)

WASHINGTON, D.C. (Callaway Climate Insights) — Nearly 30 years ago, Russell Batson, a former congressional aide with a tongue-in-cheek sense of humor and a lot of chutzpah, wrote the book on freeloading at Washington receptions.

Batson’s slender paperback volume, “Eat Free in D.C.: A Guide to Budget-Neutral Dining in Our Nation’s Capital,” quickly became must-reading for impoverished interns on Capitol Hill and moochers elsewhere.

Among the key takeaways: Crash events thrown by deep-pocketed interest groups like the oil and gas lobby (featuring top-shelf booze and fresh seafood) and avoid those sponsored by environmental groups (featuring club soda and cheese cubes on toothpicks).

What does this have to do with climate finance and the fate of the planet? Quite a bit, actually.

Decades after Batson was foraging for free food, three things are still true in Washington: Money talks. Fossil fuel interests raise and spend more of it than environmental groups. And there’s no climate superlobby to do for Earth what the NRA does for guns, AARP does for seniors and AIPAC does for Israel.

In a city where it’s easier to block legislation than to enact it, and where it’s much easier to pass tax cuts than tax hikes, those are significant obstacles to President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion infrastructure and clean power proposal, at least in its current form.

Those are also obstacles to efforts to tax carbon as a way to make green-energy sources more competitive and to stop greenhouse-gas emitters from using the atmosphere as a free waste dump. (The influential American Petroleum Institute has announced support for a price on carbon, presumably as a way to keep a seat at the table and fend off more onerous regulations.)

To be sure, the financial gap between fossil fuel interests and environmental groups has narrowed considerably in recent years. Environmental money has become a more significant part of the Democratic funding base, and pressure from the environmental donor class helped kill the controversial Keystone Pipeline project. Even so, the financial disparity remains substantial.

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, oil and gas interests made $139 million in political contributions in the 2020 election cycle, nearly three times the $48 million donated by environmental interests.

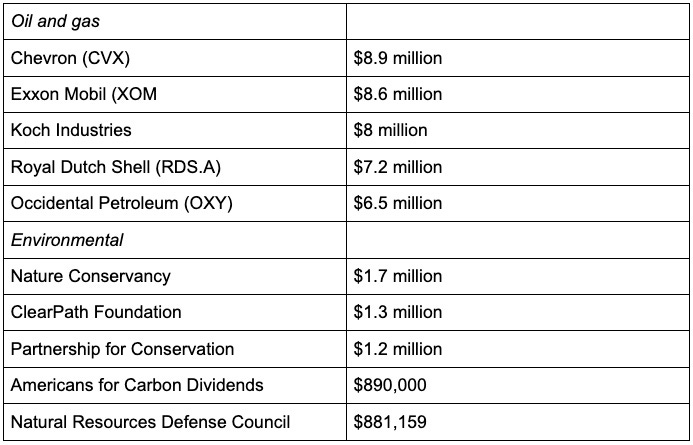

The differential in lobbying expenses last year was even more stark: $39 million for the top five energy companies versus $6 million for the top five environmental groups. (See chart below.)

True, this didn’t stop Biden from winning the White House or the Democrats from narrowly taking control of the Senate and clinging to the House. Biden and the Democrats “made the calculation — correctly — that climate was a political winning issue in the campaign,” says former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz. “That is a big shift. The public is ready for this. The public wants it.”

Maybe so, but Biden’s main appeal to many voters was that he isn’t Donald Trump, and powerful interest groups can thwart measures that have wide popular support. A recent poll shows 65% of Americans back stricter gun laws, but since 1994 the NRA has been able to fend off any major federal restrictions on firearms, including universal background checks and proposed bans on assault-style weapons.

A former top environmental lobbyist tells me that green groups had “NRA envy” about the rifle association’s political clout. Rather than a new climate supergroup, this lobbyist believes that what’s needed is a grand coalition that sets aside rivalries and brings together environmental activists, clean-energy entrepreneurs, and industries (insurance, reinsurance, health care, agriculture, recreation and coastal real estate, to name a few) harmed by global warming.

Such a coalition could help convince the public that the problem is urgent, mobilize voters to support candidates who care about it, twist the arms of reluctant lawmakers on key votes — and raise the money to make it all happen.

Rather than try to compete financially with fossil fuel interests, some environmentalists are focused on trying to limit money in politics. That, however, would likely require a constitutional amendment to overturn the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision — a long shot at best.

For now, to paraphrase former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, climate activists — and the billionaires who love them — need to fight within the political system we have, not the one we might want or wish to have at a later time.

That means creating either a grand coalition or climate superlobby to promote climate-friendly policies and stop the fossil fuel companies from feeding at the trough in D.C. The recently launched American Clean Power Association, bringing together the Balkanized renewable energy industry, is at least a small step in that direction.

Being competitive in Washington also means supplementing science and idealism with cold, hard campaign cash. Since one way to lawmakers’ hearts is through their stomachs, some Grey Goose and jumbo shrimp wouldn’t hurt, either.