Silicon Valley's environmental tree: from Fairchild Semi to Locus Technologies

A founder traces the history of today's environmental software to the dawn of the electronics age, and the father of all tech companies itself.

By Neno Duplan

(Neno Duplan is the founder and CEO of Locus Technologies.)

MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif. (Callaway Climate Insights) — This story is about lineage, particularly the linkage between Fairchild Semiconductor, its successors and offshoots, and Locus Technologies. It is about how high-tech manufacturers have potentially forever affected Silicon Valley's subsurface soil and aquifers and how one company, born out of necessity in the offices of Fairchild, has helped many similar industries throughout the world become better stewards of the environment. It is the story of Fairchild Semiconductor and Locus Technologies.

Today, Silicon Valley looks like a clean, dreamy officescape with manicured lawns and inviting campuses. But these beautiful views above ground hide a legacy of impacted soils and aquifers underground. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Silicon Valley companies manufactured the semiconductors that drive our computers and other modern-day electronics, from smartphones to satellites. Unfortunately, this industrial boom also created some of the largest environmental contamination sites in America. For years, journalists have written about the successes of Silicon Valley companies, but much less has been published about the side effects of this success. For a region where an incredible amount of capital has been spent to create new companies and develop real estate, this aspect of Silicon Valley's history remains surprising to many people who live elsewhere. The transition of this area from orchards, small towns, and quiet neighborhoods to its present state as an epicenter of high technology and innovation all started with Fairchild Semiconductor.

In his recent book The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future, author Sebastian Mallaby states, “By 2014, an astonishing 70 percent of the publicly traded tech companies in Silicon Valley could trace their lineage to Fairchild Semiconductor.” Intel INTC 0.00%↑, National Semiconductor, AMD AMD 0.00%↑ , Apple AAPL 0.00%↑ , Teledyne, Tandem Computer, Genentech, Atari, Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins, Oracle ORCL 0.00%↑ , Airtouch, and even Google GOOGL 0.00%↑ are just some of the companies that can trace their birth back to Fairchild. Descendant companies are frequently called Fairchildren. The Computer History Museum in Mountain View calls it a Trillion Dollar Startup and depicts a Fairchild Family tree as one of its flagship exhibits.

Fairchild was pivotal in shaping the modern electronics industry. Founded in 1957, the company was one of the inventors and pioneered various industry-leading semiconductor products, including transistors, LEDs, and integrated circuits (ICs). They also pioneered innovative manufacturing processes for semiconductors and ICs. The story of Fairchild began when a group of brilliant engineers and scientists, known as the “Traitorous Eight,” broke away from Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory in Mountain View, Calf. to form Fairchild Semiconductor.

Fairchild’s founders knew the future would be built on silicon-and-wire devices using simple sand and metal wire materials that cost almost nothing. They did not realize that the chemicals and technology they employed to turn sand-and-wire into silicon chips would cost their companies dearly in terms of money, reputation, and environmental damage. Their story parallels the nuclear power industry, which solved many potential energy and emissions issues but created another set of complex environmental challenges. No medicine comes without side effects. I will get back to the contamination issue in a few paragraphs.

Locus is not publicly traded or in the semiconductor manufacturing business. Like Fairchild, the story of Locus begins in Silicon Valley 20 years later, in 1997, when several engineers and I broke away from a consulting company devoid of vision to form Locus. We aimed to create cloud-based software, better known today as software as a service (SaaS), to change how the world manages and organizes emissions data and environmental compliance information. Fairchild was Locus’s first customer.

Fairchild provided a fertile environment to launch Locus. First, Fairchild and its successor companies left extensive environmental impacts on many neighborhoods from New York to California, where their plants operated. Second, many successor companies with lineage to Fairchild indirectly gave us a set of unique technologies that Locus put to good use to manage the environmental sites that Fairchild and its successors left behind. With its environmental contamination domain expertise, Locus effectively used these new software technologies to organize the vast amount of information gathered from Fairchild's contaminated sites and emissions sources.

Having the data in the cloud software enabled Locus to speed up the sites’ cleanup and enact a verifiable long-term monitoring and reporting program.

Fast forward to the present, Locus’s customer base uses the same underlying technology that Locus developed and first deployed in Silicon Valley to store, analyze, visualize, and report on their environmental data. Across all customers, data from over 1.5 million locations and over 500 million results are stored in Locus SaaS. In these times when a movie about Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory, is breaking box office records, it is worth mentioning that LANL has used Locus SaaS for over a decade to assess the nature and extent of on-site and off-site contamination resulting from the building of the atomic bomb and other activities.

Fairchild Semiconductor contamination

It might not be a familiar name like Apple or Google, but Fairchild pioneered the technology that powers all our electronics. The silicon chip manufacturing technology developed by Fairchild and its descendants turned a quiet agricultural region south of San Francisco into the industrial manufacturing center better known as Silicon Valley. From a distance, Silicon Valley is the envy of every community seeking to lure the high-technology industry. Its myriad electronics companies employ over 100,000 workers in what most people consider one of the nation’s cleanest industries — no dangerous assembly lines, belching smokestacks, or rivers turned brown by contaminants.

Contamination discovery

During the ‘60s through the early ‘90s, chipmakers, including Fairchild, Intel, and Raytheon, slowly leaked volatile organic compounds, VOCs, into the soil in Mountain View and surrounding communities. The main culprit is underground storage tanks made of materials incompatible with the aggressive solvents these companies stored in them. Concentrated leakages from these tanks formed extensive plumes that penetrated up to 500 feet beneath the ground surface and contaminated several aquifers by following the pathways of former agricultural wells in the region. The plumes ranged from a few hundred feet to 10 miles in length. Drinking water, regional creeks, streams, and estuary lands were all affected. The result left the technology heartland with an extended network of contaminated subsurface, groundwater, and later indoor air.

The environmental degradation of the valley caused by the semiconductor manufacturers was only discovered after elevated cancer rates emerged in the area in the 1980s. Subsequent subsurface investigations revealed that all was not well in the Valley. The existence of the contamination prompted significant environmental concerns and regulatory actions, leading to cleanup efforts and many legal disputes.

Companies in the region, including Fairchild, were required to take responsibility for remediation efforts and address the contamination problems. Some 29 EPA Superfund sites were identified, the highest density of such sites anywhere in the nation. The most notorious are the former Fairchild plants. Other Superfund sites are found where Intel, IBM IBM 0.00%↑ , Varian, Hewlett-Packard, Raytheon, Applied Materials AMAT 0.00%↑ , and National Semiconductor had facilities. In all, the industry is responsible for the leakage of tens of thousands of gallons of organic solvents and other toxic contaminants into the groundwater and air of Silicon Valley.

New campuses and some headquarters of today’s famous companies like Apple, Intel, Google, NASA, and Hewlett Packard now sit atop some of these designated Superfund sites or their underground plumes. The below-ground contamination and indoor air quality at these facilities must be continuously monitored. Take the Intersil Inc./Siemens Components Superfund site, for example. The site sits across the street from Apple's circular new campus. Semiconductors were manufactured on this 15-acre site in the 1980s.

To remediate the contamination caused by this activity, EPA reports that “twenty-three soil vapor extraction wells have been built, along with a carbon adsorption treatment facility. Groundwater is being extracted, treated by air stripping, and discharged into Calabazas Creek.”

In less than 30 years, the Valley has gone from farmland and other low impact uses to the site of a technological revolution to a massive cluster of Superfund cleanup sites. While Fairchild sparked the greatest legal accumulation of wealth in history, it created significant environmental impacts in the region that was pristine agricultural land before redevelopment.

Over the years, the EPA has ordered various cleanup and mitigation measures to address Silicon Valley's groundwater contamination. Reclamation projects have transported polluted soils to federal hazardous waste sites. These projects were followed up by groundwater pumping, treatment, re-injection, and monitoring programs.

Semiconductor manufacturing process

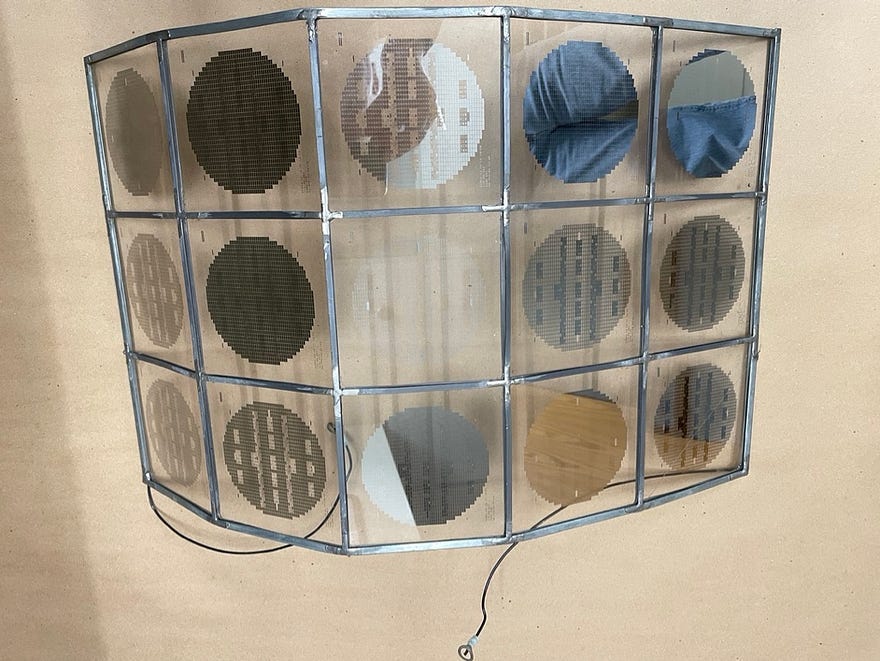

It started with an ingot of super-pure silicon, created by pulling a “seed crystal” through a vat of molten silicon until it formed a thick, multilayered “ingot,” like the one seen in a Fairchild promotional video from 1967,

The sausage-shaped ingots were shaved into thin wafers and polished using several chemicals. After that came the process of printing transistors into the chips, which required degreasers and solvents, including the sweet-smelling trichloroethylene (TCE). TCE was classified as a carcinogen by the EPA in 2005 and would later be found in groundwater around Silicon Valley after leaking from dozens of manufacturing sites.

Schlumberger acquires Fairchild

Schlumberger SLB 0.00%↑ is a major oilfield services company that provides technology, information solutions, and other services to the oil and gas industry. In 1979 Schlumberger acquired Fairchild hoping that Fairchild's semiconductor technology would give them the upper hand in their core business. But the acquisition was Schlumberger's disastrous eight-year mistaken plunge into the semiconductor business. It has cost Schlumberger hundreds of millions of dollars in Fairchild's cleanup costs and is still ongoing. Schlumberger was familiar with environmental issues associated with their oil production sites. But they never encountered anything comparable to the environmental nightmare that Fairchild’s activities left behind: many square miles of commingled groundwater plumes of highly persistent chemicals in urbanized settings that will take hundreds of years to remediate. The acquisition also proved to be a clash of cultures — and an expensive lesson for Schlumberger.

Schlumberger acquired Fairchild in the belief that they could quickly transfer the technological prowess of Fairchild to their downhole oil exploration technologies. That transfer of technology did not happen. Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore were already Silicon Valley legends when they left Fairchild and founded Intel in 1968. The two men had been among the founders of Fairchild. By the time of Schlumberger’s acquisition of Fairchild, most of the talent and brain power behind Fairchild had left to create new startups like Intel and National Semiconductor. It is even more ironic that Schlumberger’s oil engineers from Houston and elsewhere were helpless in dealing with the environmental issues that Fairchild left behind. There was no reverse technology transfer either, because Schlumberger did not possess the technology needed to clean up Fairchild’s contamination.

In 1987 Schlumberger sold Fairchild to National Semiconductor for a fraction of the price they had paid. Schlumberger retained the environmental liability of Fairchild, which continues to this date.

Silicon Valley cleanup remains a complex and ongoing environmental challenge in the region.

With the mandated cleanup comes the challenge of managing the data associated with the discovery, remediation, treatment, and long-term monitoring of sites. We are talking about lots of data. Big data. That is where Locus steps in.

Enter Locus

On 11 April 1997, a few colleagues and I gathered in an attorney’s office at One Front St. in downtown San Francisco to begin the Locus journey. We had come to know one another while working as consultants to Fairchild and Schlumberger. Our shared experiences led us to found Locus, an environmental software and services company that provides environmental data management and compliance solutions. Locus did not start as a blank slate with just a set of goals and visions. It was kickstarted and grew from my work as a research associate at Carnegie Mellon in the 1980s, where I developed a prototype system for environmental information management and display using microcomputers.

After we created Locus, it was a logical choice for Fairchild management to support us as we had experience with their sites and had founded the company to automate the data management and reporting activities stemming from the ongoing investigation programs at the Fairchild sites. At the time, information management proved overwhelming for Fairchild and other responsible parties, including Raytheon, Intel, and others, most of whom realized their spreadsheet-armed consultants' tools were not up to the task. Data management and sharing was a big challenge costing them a fortune. Locus’s experience and increasingly powerful cloud-based data collection, analysis, visualization, and reporting tools would eventually fill an enormous gap in Fairchild's and Schlumberger's investigative and remediation programs.

Early Locus successes

Not only did Locus organize Fairchild’s data and reporting over time, it also automated Fairchild’s data collection activities using various wired and wireless technologies and then replaced SCADA systems with web-based technologies long before the terms SaaS or IoT were coined. Close relationships between Locus and Fairchild managers grew so rapidly that Fairchild let us use their offices as our initial headquarters. The company was born and immediately tested with enormous real-world challenges. Locus was christened by fire.

When contamination was first discovered at Fairchild’s South San Jose site, the company didn't know they had such a big problem then. But they were very responsible corporate citizens. After discovery, they immediately tried to prevent the spread of contaminants. Locus aided their efforts by providing them with some pretty exciting technologies. In an interview with Silicon Valley Business Journal, Tom Jones, who managed Fairchild's environmental liability, said: ".. not using Locus is a mistake most companies can't afford to make. In environmental cleanup technology, disciplines are intertwined. I don't know if it was by happenstance or design, but Locus has each of the disciplines represented in its group," he said.

In its story of the Fairchild cleanup success at the South San Jose site, the San Jose Mercury News published an article titled “From Superfund to Supermarket” in September 1997. They wrote: “After a 15-year groundwater cleanup, San Jose's Fairchild site is deemed safe enough to be reborn as a shopping center. After $40 million in cleanup work and billions of gallons of groundwater pumped and treated, the stigmatized site is so clean now they say they’d take their own kids to shop there. Nearly two decades ago, the Fairchild leak touched off a major controversy, leading to tough new laws about hazardous chemicals in California. Officials for Schlumberger Ltd., the French oil equipment company that bought Fairchild in 1979 in what proved to be a disastrous business move, say that after spending $40 million, they are still spending $483,000 a year to squeeze the final parts per billion from groundwater no one drinks.”

Funding Locus

The contamination that Fairchild and its successor companies created made Locus possible and fueled its initial growth. We did not need venture capital money as Fairchild and many Silicon Valley startups did at their inception. We measured our success by how many records we amassed in our cloud-based multi-tenant database. Our vision for better global environmental stewardship focused on empowering organizations to improve their tracking and mitigate the environmental impact of their activities. That vision has come to fruition in Locus’s work with some of the world's largest companies and government organizations.

Many in our greed-driven culture, particularly in Silicon Valley, value company founders based on how much venture capital or private equity money they raise or how quickly their companies grow over founders who bootstrap their companies from nothing, preparing them for a long and steady growth.

We always believed that how much funding a startup company raised or how quickly it grew is the wrong metric to measure a company's success. For a company set to deal with planetary existential problems that require a long ramp-up time, having its customers have skin in the game is far more critical. That is the only way to determine their seriousness in addressing environmental commitments. If the customer does not believe, they will not successfully digitize their environmental, health, and safety (EHS) and environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) activities. If we had to invest more money in marketing and sales organization versus R+D, we would not have created a product with a compelling reason for customers to buy it.

At every stage of the startup, some actions are “right” for the startup in that they maximize return on time, money, and effort. That is precisely what we did with Locus to weather several recessions and market downfalls. While bootstrapping techniques are not just limited to funding, they also apply to how companies are run. We created a built-to-last, low-burn startup by maximizing our resources on tools and applications that brought real value to our customers and avoided those that the market did not immediately need or those that required external resources. Bootstrapping provided Locus with a strategic roadmap for achieving sustainability through customer funding (i.e., charging customers) — if it is to be important for Locus, it must be important for the customer first. If it is important for customers, they must pay for it and have skin in the game. With this simple philosophy in mind, Locus was born and built.

Locus’s bootstrapping strategy game plan assumed that once you build up a solid customer base, you can turn to your user community for suggestions on improving your product, a practice known as crowdsourcing. This approach provoked a rapid and funded expansion of Locus’s products in the marketplace.

Fairchild's projects were our initial source of funding. We became profitable in the first year after inception. Other companies that inherited Fairchild’s environmental liabilities also became Locus’s customers. These included Schlumberger, Intel, Raytheon, and Varian, to mention a few. Armed with the experience we gained at these semiconductor manufacturing sites and with internet technology exploding around us, Locus was ready to conquer the environmental information management space and, in the process, create a new industry, EHS compliance, and ESG reporting SaaS.

A bigger picture unified SaaS platform

Locus recognized an opportunity to think bigger about managing environmental data and realized early on that what would drive our business and growth is not contaminated sites but the bigger picture related to sustainability and climate change. In 1999, Locus started offering the first cloud-based environmental data management software. Over the past 15 years, that software has expanded to cover more and more aspects of environmental compliance, sustainability, energy, water quality, air emissions, mitigation, and stewardship for the companies that use it.

Locus wants companies to have the tools to be proactive in their environmental stewardship; to date, most organizations have incorporated environmental policies reactively. Much of the environmental industry is driven by regulations where few companies have a genuine environmental policy that goes beyond greenwashing for public relations. This is particularly true in sustainability, where we need regulations that bite.

However, Locus is looking at longer-term applications for its company’s SaaS by considering the role of technology in combating our collective environmental challenges. With the heavy toll of human activities on the planet, how can we harness the scientific methodology of gathering and analyzing data to make the changes we will need to make to change course? Gathering and tracking all of these data, examining them in the aggregate, and understanding how all of our activities are affecting climate change, habitat erosion, and public health issues, can, in the end, help society address these challenges collectively. Without the data measuring what our emissions are doing and at what rate, without the facts, it will be impossible to mitigate the damage at the correct scale.

While other environmental software companies have come and gone — often after getting a lot of press, only to fizzle out on broken promises and dried-up funding, Locus has never wavered from its path to provide these services to corporations and government agencies. Despite the absence of a flashy PR machine and VC funding, Locus has become a profitable, independent, and visionary organization, now considered one of the top environmental software companies in the world.

The company’s strategic focus has always been to deliver intelligent, well-designed software applications that add value to customers' bottom lines. The success of these applications is rooted in the Locus team’s deep environmental domain and content experience, its proven multi-tenant SaaS architecture, and its view that customers that own their data maintain a competitive advantage over those that don’t.

While most environmental software firms have focused on tracking one area of emissions, such as greenhouse gasses (GHG), Locus has built the most comprehensive SaaS platform for managing compliance and organizing environmental and resource data and information. Creating a software platform takes work, as it is an evolutionary process. In that context, let me share a roadmap offered by Geoffrey Moore on how platforms typically evolve into being: “Keep in mind that a critical component of any evolutionary journey is that the organism thrives at each stage. You cannot take a living being offline, reengineer it, and then bring it back to life. Nor can you design a complex being from scratch and launch it. Everything has to be built off of something pre-existing that has succeeded in its evolution to get as far as it got.”

The evolution of Locus SaaS continues in its 25th year. Many startups fail to reach maturity in this business due to an inability to embrace rather than develop workarounds for such evolutionary processes. And it is also the reason why roll ups don't work. A rollup merger is when an investor, such as a private equity firm, buys up companies in the same market and merges them, hoping that is better positioned to enjoy economies of scale.

With Locus, customers can manage, search, report, maintain, and preserve all the required documentation and data for environmental compliance and sustainability management on a single platform. Everyone associated with the high-tech industry knows the value of becoming a platform. Locus migrated to a platform architecture initially to simplify the maintenance of our suite of applications as well as to unify the user interface into a potpourri of products. Later, we opened up our platform to major customers and partners. These enterprises have the in-house resources to build differentiating, proprietary applications on the Locus Platform. They further expand our portfolio of apps as some of the things they want to do are explicitly outside our roadmap.

Using Locus, customers, and their consultants can quickly configure and deploy a comprehensive set of applications using intuitive drag-and-drop tools and no-code development for building input forms, workflows, calculations, and dashboards. Locus will provide. Another main component of Locus’s offerings is the ease with which Locus integrates with other enterprise software — part of the big picture for risk management, compliance, and health and safety software.

The resulting Locus applications help companies better record, track, manage, analyze, and share water, air, energy, sustainability, and compliance management information, all from a single system of record.

Fairchild Locus nexus

Before concluding our story, let’s consider the nature of the tie that binds Fairchild and Locus.

Fairchild and many of its successors gave birth to semiconductors used in manufacturing computers and other electronics. The manufacturing of these semiconductors left behind widespread contamination in Silicon Valley. Other companies, some located in the valley and others elsewhere, used these technologies to create increasingly sophisticated and powerful software. This software runs computers and builds applications, notably web-based data management systems. Over time, computers became ever more powerful and varied, resulting in the emergence of, among others, servers and personal computers. Locus used these companies’ products, many with direct or indirect links to Fairchild, to create a multi-tenant SaaS platform that runs on cloud-based servers and is accessed over the web. Customers with emissions sources, contaminated sites, or those serious about managing their sustainability based on scientific data in the Valley and elsewhere have adopted various iterations of Locus’s SaaS to manage their environmental liabilities and emissions. In short, Fairchild’s descendants gave birth to the tools that Locus used to build a SaaS platform to manage the contamination that Fairchild had left behind and much more.

We should recognize Fairchild’s more direct role in Locus’s growth and development. Locus needed contaminated sites to design and test its SaaS tools. Fairchild provided such sites in spades. There were many of them, but they often overlapped, and the contamination was widespread, affecting more than one media. In addition, Fairchild always had neighbors with similar problems resulting in commingled plumes of contaminants. This created another opportunity for Locus to build collaborative SaaS and share a single software of record across multiple customers. Only the web could offer this collaboration based on emerging social media technologies. Locus customers benefited from incorporating those technologies in our SaaS early in developing our flagship products.

There is one other element that contributed to the growth and success of Locus. Our key staff came to Locus with dozens of years of consultant-based environmental data management and compliance experience and first-hand knowledge of the difficulties and frustrations of homegrown solutions involving spreadsheets and siloed custom software. We knew Excel and PC-based tools would not cut it. Only a web-based system accessible from any location that avoided the need to deploy updates to individual computers or client-based servers would work. That is the path we headed down and set the stage for our success.

Schlumberger eventually acquired Fairchild. When it did so, it also acquired the company's problems, which snowballed so much that our team managed all of Schlumberger's Fairchild contaminated sites in California and one in New York. Our first offices were at Fairchild's former Headquarters. Today’s Locus headquarters is at the former Fairchild facility, and our address is 299 Fairchild Drive. Believe it or not, many of our furniture still have tags that read “Property of Fairchild Semiconductor.”

Later successes

Soon after Locus’s success with Fairchild, we started signing up many Fortune 500 customers. The ultimate validation of our technology, staying power and security in the cloud, was an award for data management from the Los Alamos National Laboratory. After storing its data in multiple systems for years, Los Alamos scrapped them all and standardized them on Locus’s cloud-based platform.

Los Alamos uses Locus SaaS to manage environmental compliance and monitoring activities for multiple stakeholders on a nearly 40-square-mile site where radioactive and chemical contamination occurred during The Manhattan Project and subsequent decades of nuclear-weapon production, research, and testing. It’s one of the most massive environmental monitoring programs on Earth, but all information is available in real time to the public, with no password required. Locus’s scalable and intelligent database can now analyze billions of records via self-learning algorithms and package the insights for immediate use. The extensive data set that once was heavily siloed can be accessed seamlessly without depending on data stewards.

Over the 27 years following its birth, Locus’s founders and many who later joined us would build a company based on three breakthrough goals:

In place of client-server and silo systems, offer organizations multi-tenant cloud software and applications to manage their environmental compliance and sustainability

Create a subscription business model and

Build an integrated model for emissions and environmental information management

Through these ideas, Locus would revolutionize the EHS compliance and sustainability industries.

What started with Fairchild’s sites 27 years ago, Locus continues its revolution, offering integrated EHS and ESG SaaS, mobile, Internet of Things (IoT), and AI technologies for companies of every size and industry.

Locus has changed how companies manage their environmental liability and emissions and, at the same time, improved companies’ means to manage their impacts on the climate and environment. Just as it did for contaminated sites, Locus pioneered the SaaS model in the EHS and ESG workspaces, continuing its commitment to never install its software on customers' premises.

Locus recently broke new ground by releasing the first Visual Calculation Engine for ESG Reporting. Locus’s visual calculation engine helps companies quickly set up and view their entire ESG data collection and reporting program, enabling full transparency and financial-grade auditability. Competitors merge and disappear as the industry evolves and new markets emerge and grow. Locus remains a constant in the environmental space, an innovative and independent pioneer.

Today, Locus is a mature environmental SaaS and service company. Locus’s vision for better global environmental stewardship has remained the same since its inception. We focus on empowering organizations by helping them track and mitigate the environmental impact of their activities so they avoid repeating the mistakes of Fairchild. That vision has come to fruition. Some of the world’s largest companies and government organizations use Locus’s software offerings. Locus’s SaaS has been ahead of the curve in helping private and public organizations manage their water quality, EHS compliance, or ESG reporting and turn their environmental information into a competitive advantage in their operating models.

The level and extent of environmental contamination left by Fairchild and other semiconductor manufacturers is regrettable. Yet out of this morass of TCE-impacted plumes and subsurface soils was born a company whose goal was to provide its clients with the tools to assess, monitor, analyze, and to the extent possible, identify mitigative measures. This company is Locus Technologies.

Editor’s note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of David Callaway or Callaway Climate Insights.