From cannons to cognac, the iconic history of The French 75

Jack Hamilton explores the Great War history of one of France's greatest cocktail gifts to the world.

(John Maxwell Hamilton is a former foreign correspondent and the Hopkins P. Breazeale Professor in Louisiana State University’s Manship School of Mass Communication and a Global Fellow in the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. His most recent book, Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of Government Propaganda, won the Goldsmith Prize.)

WASHINGTON, D.C. (Callaway Climate Insights) — The nexus of climate change and financial investing is a matter of deeply serious contemporary concern. That is why I find it so satisfying to write columns for Callaway Climate Insights.

But even as we push ahead to make the planet environmentally sustainable and prosperous, we all take time to kick off our shoes and rest. In my case recently that time-out has been to hoist — or perhaps I should say experiment — with a cocktail, the French 75.

The experimentation has been necessitated, first of all, by the fact that the cocktail comes in many versions — it may be the most elastic cocktail ever made — and, second, because during the workday I was writing its history, which came out as a book recently.

David Callaway, the founder and editor of this news service, has suggested that I summarize the book’s fascinating history. I do that below and throw in a life lesson from my exploration of the drink.

The history, in brief

On a rainy Sunday morning, Feb. 7, 1915, women fanned out across France carrying emblems of the 75 mm cannon. The fast-firing weapon, considered the first modern artillery piece, had helped save Paris from the Germans a few months earlier and was now firing its deadly rounds on battlefields across the country.

Passersby on that Sunday morning dropped coins in the women’s baskets and plucked out the French 75 medals, which were suspended from ribbons with the red, white, and blue colors of the French flag.

Twenty-two million medals ended up on lapels that day. The donated coins, used for care packages sent to soldiers at the front, piled up to nearly five and a half million francs. “The glorification of the 75 gave our soldiers a sense of well-being. It also created a great feeling of fraternal union among all French people,” an artilleryman wrote in Notre 75: Une Merveille du Génie Français, a book that appeared shortly after the event and was itself an act of propaganda.

A poem Notre 75 proclaimed the gun “imposes itself on our thoughts/The name of the glorious canon.” In the coming days the imposition of the soixante-quinze gun became ubiquitous. Images of it could be found on romantic postcards (L’Artillerie de L’Amour); posters; clocks and watches; board games; pens and sculpted inkwells; cigarette papers, cigarette cases, and cigarette lighters; plates, spoons, and coffee mugs; ersatz coffee, chocolates, wines, and spirits; spools of cotton thread; plaques; handkerchiefs, decorative boxes; padlocks; rings....

And on a new cocktail, the French 75.

Based on the best evidence available, the launching pad for the French 75 cocktail was the Opéra District of Paris. Henry Tépé, who had a bar there, is the first bartender to be mentioned by name in connection with the cocktail.

The origin of Henry’s Bar said a lot about its namesake. While presiding at the Chatham Hotel bar, his “cheery disposition and attention to work” made such a good impression that an American patron, a Southern colonel who fought in the American Civil War, staked him to his own saloon in 1890.

Henry’s Bar was called the second oldest American bar in Europe, Chatham’s being first. American bars were so called because they served cocktails, which was considered an invention from the United States.

“Square Henry,” as he came to be known, took care of the colonel when he ran out of money, and he was remembered for his kindness to others. American ambulance unit drivers and American aviators frequented his bar during the war.

Tépé’s tragic death a few months before the conflict ended in 1918 made news in the United States. The war was acutely painful for the German-born barman. As his mind slipped, he forgot to put the day’s proceeds in the safe. “Ill health and brooding,” reported a sympathetic New York Sun correspondent, led Tépé to jump out of a second-story window.

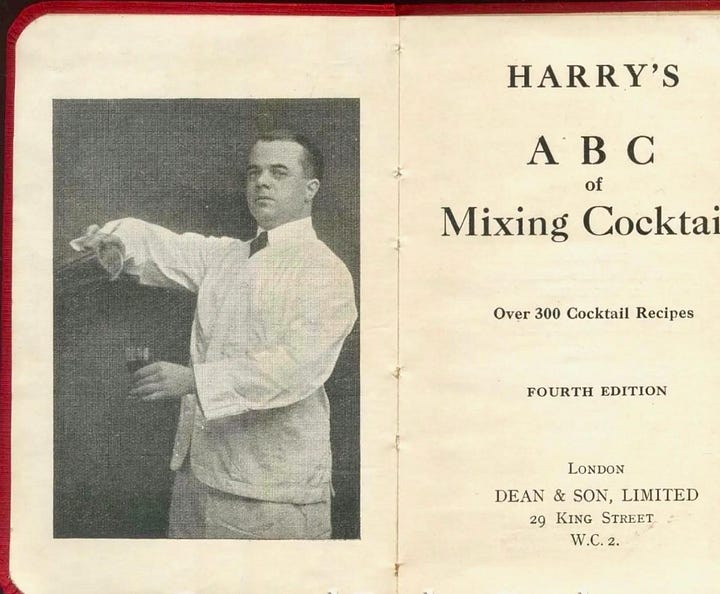

After the war, a bar around the corner from Henry’s made the drink more famous. Harry McElhone, who took over the New York Bar in 1923 and added his first name to it as Henry did to his, wrote the ABC of Mixing Cocktails. It contained a recipe for a Calvados-and-gin version that is no longer made, so far as I know, except in our kitchen. Harry’s now serves a slightly different version. I will give the instructions for making the original Harry’s presently.

McElhone’s recipe was not the first. And other recipes would come along over the years. Celebrated barman Harry Craddock of the American Bar at the Savoy Hotel established a champagne-and-gin iteration that remains popular today.

As time passed, the Great War origins of the drink faded. Almost certainly, for instance, it was served at the private gentlemen’s Buck’s Club in London, which opened its doors in 1919. The club catered to officers who fought in the war and drank in Paris when on leave, and Harry McElhone mixed drinks there in its early days. But the club does not have the drink on the menu today, and its secretary had no idea it ever was.

Elsewhere, though, the cocktail lived on. It appeared in Casablanca (in a memorable scene, which readers should look out for when they watch the film for the hundred and first time), Riptide, and a couple of terrible John Wayne movies.

The cocktail’s movie cameos provide an important clue to its longevity. Not only was it constantly reimagined to suit contemporary tastes. Something else was also very important. It had a sexy name. If an imbiber did not know the wartime origin of the French 75, that only made it more intriguing.

To give an example how this has worked, consider the role of Arnaud’s Restaurant in the New Orleans French Quarter. To embellish its image as a cosmopolitan establishment, the proprietors renamed the bar the French 75 Bar.

Then, to ensure the makeover was complete, they invented a new version of the cocktail with Cognac and Champagne. The French 75 was an insignificant drink in New Orleans until that happened. Now it is one of the city’s iconic cocktails.

The lesson and the recipe

I had never been on the cocktail beat before pursing the French 75. I learned a lot about the drink (I’ve only scratched the surface above) and about the “Booze Arts,” as journalist and social critic H.L. Mencken termed them. He called the cocktail “the greatest of all the contributions of the American way of life to the salvation of mankind.”

But cocktails go back much further than our republic. French 75-like concoctions – brandy, sparkling wine, distilled spirits, and so forth – happened naturally, on multiple occasions in multiple places, perhaps beginning with Adam and Eve’s first-kiss in John Milton’s Paradise, where “for drink the Grape / She crushes, inoffensive moust, and meathes/ From many a berrie, and from sweet kernels prest.”

Cocktails are an expression of the earth’s bounty and humans’ capacity for invention. That’s the lesson.

And here is the recipe that I like best. I call it Harry’s Original:

One teaspoonful grenadine (5 ml)

Two dashes of absinthe

60 ml (2 oz.) Calvados

30 ml (1 oz) gin

Shake well with ice and strain into a cocktail glass. A coupe is better. No garnish.

To buy The French 75 by John Maxwell Hamilton,

https://lsupress.org/9780807181768/the-french-75/

https://www.amazon.com/French-Iconic-New-Orleans-Cocktails/dp/0807181765

Read more from Jack Hamilton:

How H.G. Wells predicted climate change, income inequality and the death of knowledge

The New Wilderness tests whether man and nature can co-exist

Follow us . . . .