Add 'internet-shaming' to carbon-cutting confusion

Mark Hulbert says that clearly, the world needs a standardized and trusted method of measuring a company’s carbon footprint.

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. (Callaway Climate Insight) — Do you know the carbon footprint of reading this column?

It’s not zero. In fact, a 2015 study by GeSI found that the internet is responsible for 2% of global greenhouse emissions.

As some have pointed out, that is similar to the carbon footprint of the aviation industry. Does that mean we should add internetskam to the word flygskam (flight shame), which Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg helped add to our lexicon?

Welcome to the complicated world of calculating which companies and industries have the largest and smallest carbon footprints.

To add to the complexity, consider that most internet companies — including the two biggest players when it comes to data centers, Google (GOOGL) and Amazon.com (AMZN) — insist that they dramatically reduce their carbon footprint through the purchase of carbon offsets. But how confident are you that those offsets really do what they’re supposed to?

I ask because a ProPublica study last year found that, in many cases, “carbon credits hadn’t offset the amount of pollution they were supposed to, or they had brought gains that were quickly reversed or that couldn’t be accurately measured to begin with.” In what the study’s author termed an “even more inconvenient truth,” the “polluters got a guilt-free pass to keep emitting CO₂, but the forest preservation that was supposed to balance the ledger either never came or didn’t last.”

Clearly, the world needs a standardized and trusted method of measuring a company’s carbon footprint. And not just the relatively measurable emissions from its smokestacks, but the upstream and downstream carbon footprints of its operations -- its suppliers, its carbon offset efforts, and so on.

Unfortunately, while many have tried, we have arrived at Earth Day 2020 far short of that goal.

From David Callaway, read Earth Day's legacy lends post-Covid hope.

The Global Initiative for Sustainability Ratings has counted more than 125 organizations that produce ESG ratings of one sort or another. And as has been pointed out many times before — but nevertheless bears repeating — there is less than universal agreement between those ratings.

This was well illustrated by a study last year by State Street Global Advisors into the ESG ratings of the stocks in the MSCI World Index. Specifically, the study focused on ratings provided by four of the leading providers of such ratings:

MSCI

Sustainalytics (which this week announced it was being acquired by Morningstar)

RobecoSAM (whose ESG ratings division was acquired by S&P Global in January)

Bloomberg ESG

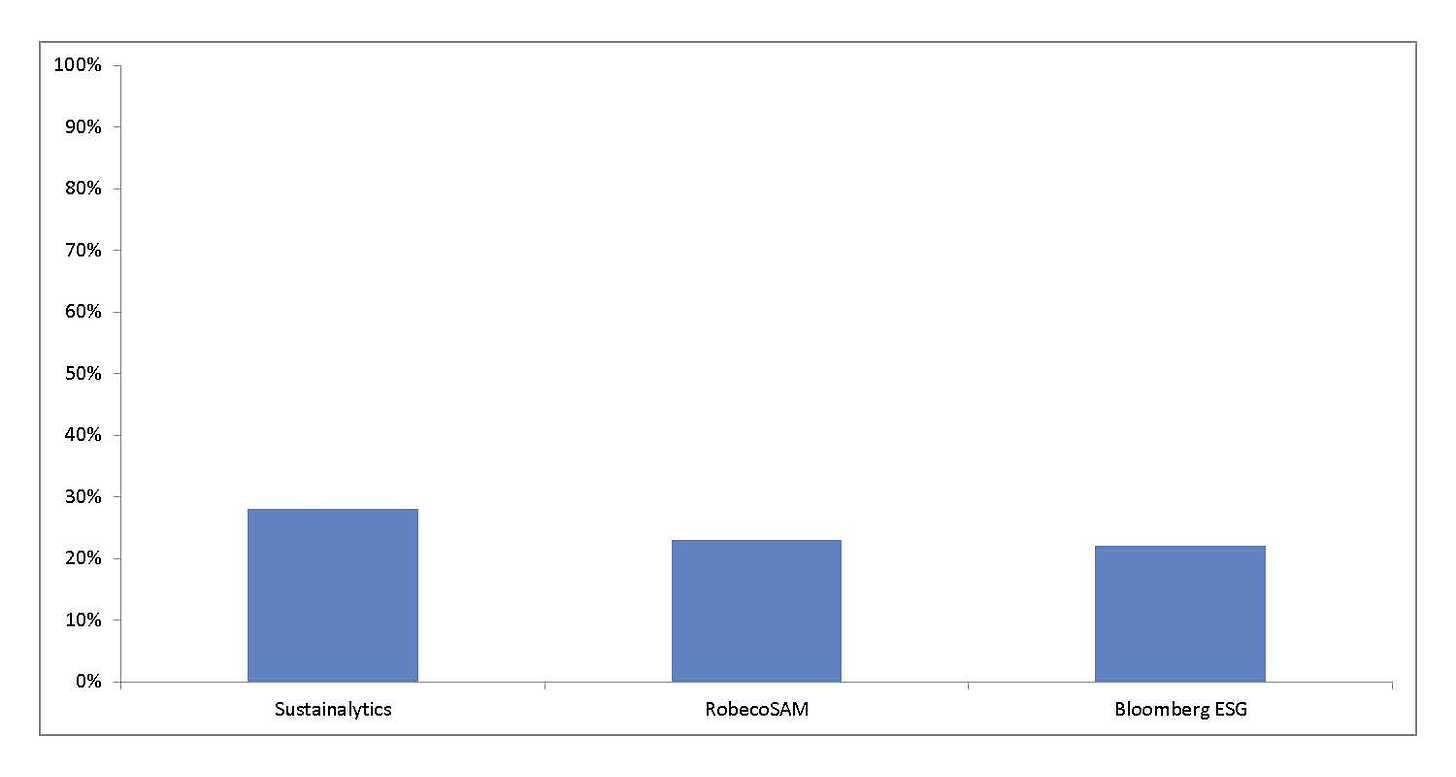

The attached chart plots a statistic known as the r-squared of the correlation between MSCI’s ESG Ratings and those of the other three. (To review, the r-squared measures the degree to which one ranking explains or predicts another. If two ratings were identical, then the r-squared would be 100%.) Notice that the r-squareds are all quite low, ranging from 22% to 28%.

Little agreement on what ESG means

Degree of correlation* between agency's ESG ratings and those of MSCI**

* As measured by the r-squared

** For stocks in the MSCI World Index

Underlying data: State Street Global Advisors

Cynicism or realism?

On the one hand, you could view this widespread disagreement over companies’ ESG ratings as the benign outcome of good faith efforts to tackle an undeniably complex task. The perfect is the enemy of the good, you might say. Just because it’s difficult to ascertain the myriad factors and interconnections that impact a company’s carbon footprint doesn’t mean it isn’t worth trying.

On the other hand, it’s also the case that the disarray in the ESG rating space has created more than enough room for unscrupulous companies to cynically exploit sustainability for marketing purposes — greenwashing, in other words. Ideology can be the refuge for scoundrels, after all.

This latter point of view was powerfully advanced in a recent essay by E. O. Blair, the pseudonym for a former asset manager with more than a decade’s experience. I find it curious, and troublesome, that this manager felt that he/she could only express his qualms about the ESG movement while remaining anonymous. In the essay, entitled “On Climate and Conscience,” the author wrote:

“It became clear that firms marketing ESG could gloss over the specifics and define ESG in any way that suited them. Confusing and contradictory assertions emerged across the investment landscape. Was ESG an umbrella term that included socially responsible investing and impact investing such as green bonds? Yes. Was it separate and apart from socially responsible investing? Yes. Did it fully embody responsible investing? Yes. Did it allow clients to express their values? Yes. Was it divorced from ethical considerations? Yes. Was socially responsible investing an umbrella term that incorporated ESG? Yes. ESG was a nicely malleable concept.”

What all this means is that there is no substitute to doing your homework. You can’t simply abdicate your moral/ethical/social/environmental goals to an ESG agency whose rating methodology is inscrutable. You don’t get a guilt-free pass by investing in a fund with “ESG” or “Low Carbon” in its name.

Finding companies that are genuinely reducing the world’s carbon emissions takes work.

(About the author: Mark Hulbert is an author and financial markets columnist. He is the founder of the Hulbert Financial Digest and his Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.)