Can investors really change corporate behavior?

Mark Hulbert writes that investing wasn’t designed to be an agent for social change, but there are ways investors can make a difference.

(Mark Hulbert, an author and longtime investment columnist, is the founder of the Hulbert Financial Digest; his Hulbert Ratings audits investment newsletter returns.)

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. (Callaway Climate Insights) — What’s the most effective strategy for getting companies to be more climate friendly?

The answer is anything but obvious.

Consider divestment, which is perhaps the most straightforward approach. While that certainly satisfies our personal desire not to profit from objectionable behavior, it’s not clear that it will do much to change that behavior. The mechanism by which divestment makes itself felt on a company’s bottom line is by increasing its cost of capital, and yet one academic study found that this won’t happen until at least 20% of equity investors are willing to avoid its stock.

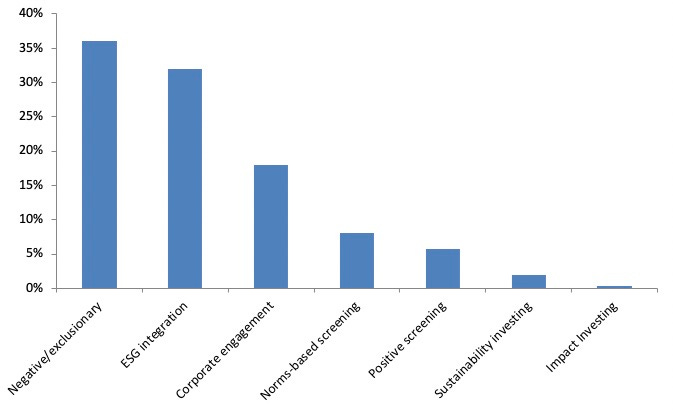

It will be difficult for any divestment campaign to come close to this 20% threshold. Though perhaps 40% of all managed global equity assets are currently invested according to one ESG principle or another, only a third of that total utilizes a divestment strategy, as you can see from the accompanying chart (courtesy of data from the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, or GSIA). Not only is this third that pursues divestment already below this threshold, it is further diluted by a focus on many different social goals — in addition to shunning climate-unfriendly companies, some divestment campaigns avoid the sin stocks such as tobacco, alcohol and gambling; others steer clear of gun makers and weapons manufacturers.

One of the few examples in U.S. market history of a successful divestment strategy is the century-long effort to avoid tobacco, which has indeed led to an increased cost of capital in the industry. Notice, however, that it is still alive and well.

And, as I’ve discussed before, one consequence of a heightened cost of capital is that investors still willing to invest in the industry earn a significantly higher return. Take tobacco stocks in the U.S. According to the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2020, one dollar invested in the U.S. market in 1900 would have grown to $58,191 by the end of last year. In contrast, one dollar invested in the tobacco industry grew to more than $8 million.

That’s a high price for avoiding sin.

Engagement

An alternative approach to altering a company’s behavior is continuing to own its stock and engaging with it in hopes of persuading it to change. And there is some evidence that engagement actually does work. One widely-cited study, which analyzed engagements with more than 600 U.S. publicly-traded companies between 1999 and 2009, found a success rate of 18%. That’s higher than for divestment campaigns.

To be sure, engagement strategies have drawbacks. They can be expensive, for example, and they’re not for short-term traders. This study found that successful campaigns on average required a sequence of two to three engagements over one to two years. Notice carefully, furthermore, that in the meantime you’re invested in companies whose policies you find objectionable.

Nevertheless, in terms of what has the greatest likelihood of changing corporate behavior, engagement strategies appear to be more effective than divestment.

Fortunately, you don’t have to choose between the two. A recent study by Scientific Beta and EDHEC, a leading French business school, recommends that we view them as mutual reinforcing. “A shareholder who engages with a company without signaling a willingness to draw a red line — by exit in case engagement fails — will enter the negotiation in a weak position: The possibility of divestment is in that sense a prerequisite for effective engagement.”

What about “ESG Integration” strategies?

It’s perhaps easier to say which ESG strategies are unlikely to lead companies to change their behavior. One prominent category of such strategies is “ESG Integration,” which GSIA defines to include “the systematic and explicit inclusion… of environmental, social and governance factors into financial analysis.” In other words, such strategies look at a multitude of factors, only some of which are related to ESG.

As you can see from this chart, this category is the second largest under the ESG umbrella.

Many ways to change the world

Prevalance of ESG approaches*

* % of total global assets invested according to ESG principles

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance review

The attraction of these strategies, of course, is that they hold out the promise of having our cake and eating it too. With them we hope to at least match the market’s return, if not beat it, while nevertheless avoiding objectionable companies — such as those that emit huge amounts of greenhouse gasses (GHG).

The reason such strategies are unlikely to lead to changed corporate behavior is a fascinating and surprising finding from the Scientific Beta/EDHEC study: These strategies in some years unwittingly lead to an increased investment in objectionable companies rather than a reduction.

This counterintuitive result is due to the non-ESG factors that these multifactor approaches take into account. Consider the momentum factor, which is one of the most popular; it calls for overweighting companies that are leading the market and underweighting those that are lagging. If an egregious GHG emitter is nevertheless outperforming the market, the approach could very well result in an increased investment in that company.

To quantify how often this might happen, the authors of the Scientific Beta/EDHEC study constructed a hypothetical multifactor mutual fund one of whose goals is to reduce the average carbon intensity of the stocks it owns. (Carbon intensity is the ratio of GHG emissions to total revenue.) They modeled their simulation on some of the many multi-factor ESG funds that are currently offered. They found that, in some calendar years, as many as two-thirds of the worst GHG emitters ended the year with a higher portfolio weight than at the beginning.

This helps to explain why, as I pointed out a couple of months ago, some leading low-carbon funds nevertheless own fossil fuel companies that are big GHG emitters.

Let me hasten to add that multifactor ESG funds have other virtues that are worthy of merit. But, from the point of view of sending consistent and unambiguous messages to corporate directors, such approaches aren’t likely to be very effective.

You may find it discouraging that investing is not an overwhelmingly effective way in which to encourage companies to engage in more climate-friendly practices. But investing wasn’t designed to be an agent for social change. It was us who had the hope that we could make lots of money while also changing the world.

This isn’t to say that investors should stop caring which companies they’re investing in. We very much should. Just because investing may not be the most effective way of bringing about a cleaner climate doesn’t mean it makes no difference. But the implication of this column is that we may want to channel our energies for climate change to other arenas besides the stock market.